# "Personalized" Learning @ASU

This is a post for students in Dr. Evan Tobias' undergraduate music education class, which I will be visiting this month to discuss this topic.

Hi! This is a webpage devoted to unpacking my approach to facilitating "personalized" learning experiences with students. I'm writing this with music education students in mind, but I'm not a music educator (at least not in the usual sense). I did all of my pre-service teacher training (including a Master's degree) in music education, but now I teach computer science. That said, the stuff I'm writing about here isn't really CS-specific, and it isn't really music-specific either. Both teaching disciplines operate more-or-less outside of the constraints that disciplines like math or English/language-arts do--while those fields are highly standardized (at least where I live they are), music and CS both operate with a level of autonomy that makes it possible for educators to do more interesting things, to consider unconventional ways of teaching and learning.

# But First, Some Context

"Personalized" learning is not unconventional or new. People have considered a "personalized" approach to teaching to be more effective than not for a hundred years, basically for as long as we have been trying to make public education work as an institution. B.F. Skinner (the person often credited with developing the idea of operant conditioning) was doing it way back when. By the time that even he got to it, it was already a well-established contrarian approach to education. The history of this part of education is really interesting; check out Teaching Machines (opens new window) by Audrey Watters if you want to learn more.

This is all to say that "personalized" learning has several decades' worth of baggage attached to it, so it's worth me providing some more specific information about what I mean when I talk about "personalized" learning in my teaching practice. People invoke "personalized" or "responsive" in all sorts of contexts. Sometimes these people are malevolent monopolists. For example, Mark Zuckerberg built a "personalized" learning tool/curriculum/platform called Summit Learning (opens new window), which ended up being the subject of student protest and activism (opens new window). These sorts of approaches are built on an assumption that 1.) we already know the things that students should learn, and 2.) that the best way to get them to learn those things is to provide them with an automated, responsive learning experience that "trains" them to meet these pre-defined goals.

This is not what I mean when I describe "personalized" learning.

# My Approach to Personalized Learning

My assumptions when I engage a group of students are these:

- I do not yet know what we should learn together

- The only way to figure out what we should learn is to talk about it

- Students often lack the domain expertise to put their goals in context

My role as the domain expert is pretty well-defined. I need to engage students in a dialogue to figure out what they are interested in exploring, and then help them put those goals in context. It's not that students don't know what's interesting to them about CS or music--it often doesn't take long for them to find themselves in these fields somehow--it's that they have trouble seeing the path from what they know now, to what they want to know in the near or distant future.

The approaches and materials below serve as scaffolds for figuring all that stuff out, and making it compatible with formalized education spaces (i.e., school).

# 1. Creating Plans

I always start by introducing students to a metaphor for learning, a metaphor which serves as a shared language for us to use as we develop and follow our personalized learning plans. Here's the metaphor in a nutshell:

You are a learner. Imagine yourself in your role as a learner in a vast, unknown stretch of wilderness. In the distance, you see something of interest--maybe it's a tower, or a mountain, or a city skyline. This "landmark" represents your goal as a learner. You traverse the wilderness by learning new things, and the things you need to encounter between now and when you arrive at the landmark is the stuff we need to cover in this class. Your job as a learner is to 1) identify a landmark to travel toward, and 2) keep track of your journey so others can follow in your footsteps, if you want. My job as an educator is to help you find the path between where you are now and that distant landmark. I've traveled these lands before, and while I may not have trekked your unique path, I can help you figure it out.

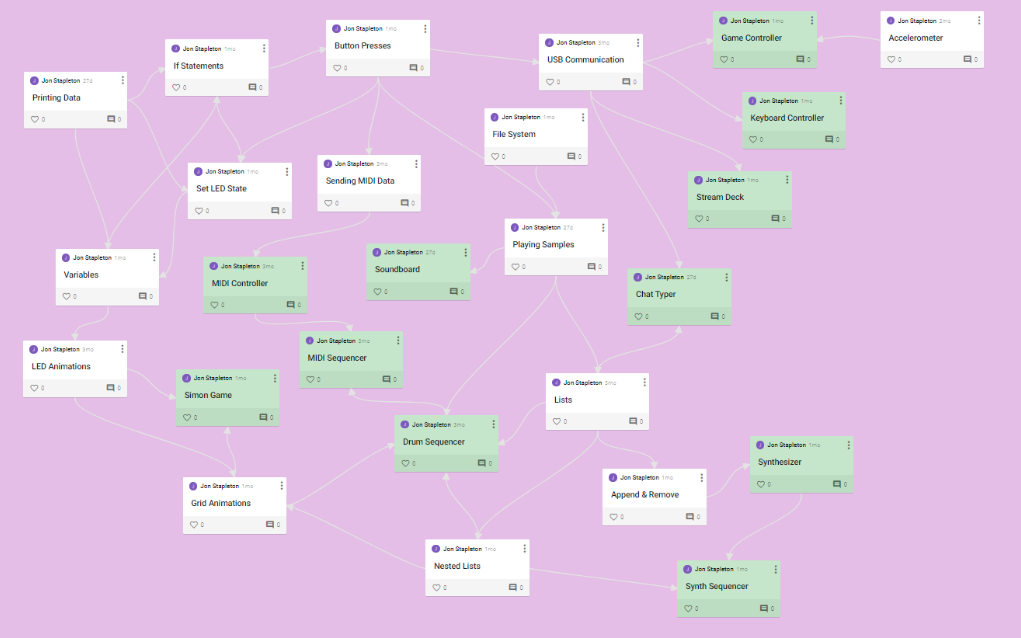

After we talk through this metaphor, I'll often show students a map of the domain of CS, or more often one small part of CS, as I see it. These maps tend to look something like this:

This particular map is based on a specific tool that students would use in my class, the Trellis M4 (opens new window). This is important: the tools you use in your class will shape the "territory" your students might explore. A horizons of a class that only has access to tubas is a lot smaller than a class that has access to computers, DAWs, and other idiomatic or trans-disciplinary music-making tools.

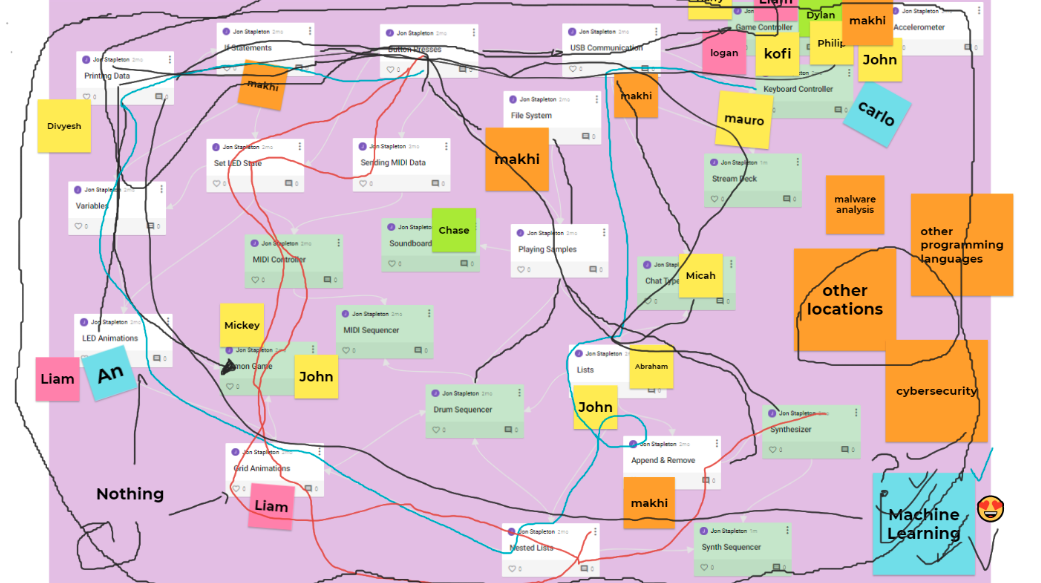

Then, I'll have students place themselves on the map--first on a topic they already know about, and then on a topic they want to know about. Finally, I'll ask them to trace a path between what they know, and what they want to know. Because the students already understand the metaphor, they also propose landmarks that aren't on the map, which is a very important step in the process. After we trace our paths, the map might look like this (apologies for the deep-fried-ness of the image, you wouldn't believe how hard it is to get your stuff after you leave a school district):

This is the beginning of a personalized learning plan.

# 2. Facilitating Student Learning

After working with maps, the students engage in generative projects where they create art in pursuit of their goals. The goal is never just to know something--it's to create something.

As we work toward these projects, the students always discover new things that they need to know about that weren't on the initial map. As we go, we add to our collective map based on what students need to meet their goals. We "blaze trails". The map evolves over time in collaboration with students; it isn't an index of things they need to learn--it's a record of learning that has come to pass.

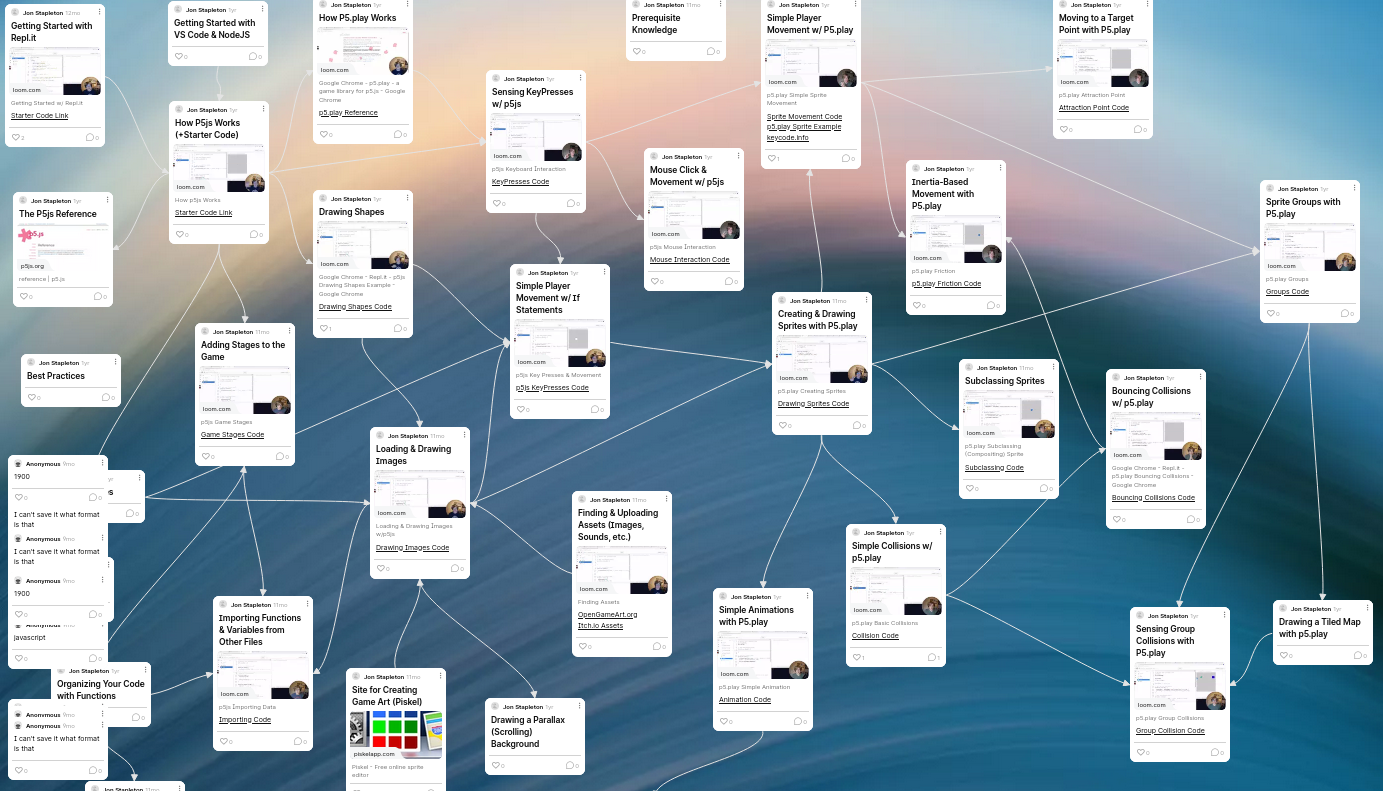

Our map starts simple (see above), but eventually grows into something that looks more like this (opens new window).

Each node on the map ends up being a little tutorial video, or a piece of direct instruction I can provide to students to help them meet their goals. Because I'm creating these in response to students' goals and needs rather than my instructional goals, they end up being a mix of generally useful bits of information (information I'm likely to re-use with future classes) and hyper-specific instruction that really only works for one learner working toward one goal.

By the end, the map is a collective expression of our learning.

# 3. Assessing Student Learning

The best way I've found to assess student learning in this context is to have them reflect on their learning in dialogue with their personalized learning path. I've found that using a metaphor like the "traveler in the wilderness" one affords students a way of engaging in metacognition in a really powerful way. That said, there are lots of approaches to assessment that are less situated. Here are some things I've done in the past that I've found useful:

# 1. Summative & Ipsative Assessment Using Menu-Based Projects

Summative assessment is an assessment of learning that takes place after most of the learning is done, and prompts students to express their learning in some sort of artifact that "sums up" their skills and knowledge. I truly despise test-based summative assessments, so pretty much every single summative assessment I've ever done has taken the form of a project.

Projects are also great for ipsative assessment, which is when you assess student knowledge in the context of their previous knowledge rather than against a common standard.

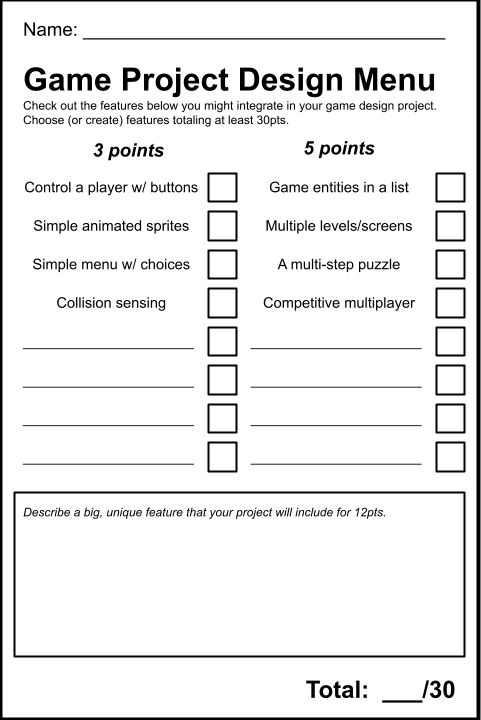

This Project Design Menu (opens new window) was really useful for helping students set individualized goals for a project, while helping me put their learning in the context of the standards of learning I needed them to acheive during my class.

Students would use this document to define their project, and then set content-based goals for how they plan to complete the project. Each thing they wanted to do in their project got a point value, and they had to "claim" a certain number of points in their plan. Then at the end of the project, we checked back in with their plans and reflected on their learning over the course of the project relative to their goals.

The summative assessment piece involves looking at their project, and deciding if it meets the standards I hoped for them to get at when they set their goals. The ipsative assessment involves having the student reflect on how they grew to meet the goals defined in the project.

# 2. Formative Assessment with Exit Tickets and Daily Goal-Setting

One of the challenges of teaching students in this hyper-adaptive way is figuring out what sort of learning experiences you need to facilitate during your time together. I tended to lean on my improvisatory teaching skills a good amount, but it's also incredibly important to engage in formative assessment to guide your work between creating plans and completing projects. One of the ways I collected this information was with Google Forms that I had students complete at the beginning and end of every class.

The form at the beginning of class had questions like:

- What is your goal for today?

- What challenges are you coming up against?

- How confident are you that you can meet the challenges you are experiencing?

- How can I support your learning today? What topics do you need help with?

The "exit ticket" at the end of class had questions like:

- What did you discover today?

- What resources do you need me to create to help you meet your goals?

- Did you make progress toward your project goals today?

- What are you stuck on?

Reviewing students' responses to these questions every day before and after class was always really illustrative. It helped inform decisions about what we should add to the map, who needed in-person help, and common themes that the whole group needed to engage with. Sometimes I would use these responses to inform learning experiences for a small group or an individual student, and sometimes I would engage the whole class in something related to their responses (there was always a surprising amount of overlap in students' individual needs).

Working with the map also led to some formative assessment moments--the ways students charted their paths toward their chosen landmarks was always incredibly informative.

# Summing Up

If you're interested in building on this work, you should think about three things as you develop your curriculum or instruction:

- Openended-ness

- Collaboration with Learners

- Generative Creativity

This is just my opinion based on my experience teaching, so take these suggestions with a grain of salt. I'll unpack each of these points below.

# Openended-ness

I always try to think of how I can create open-ended-ness in my classroom. One of my friends, Jared O'Leary (opens new window), creates Scratch curriculum (opens new window) and professional development for K-8 teachers. They often talk about how one way to measure success in those contexts is to look at how many different kinds of projects people (students and teachers) create based on their curriculum. They measure success by the number of possibilities their teaching offers to people, not by some other arbitrary skills/knowledge benchmark. I'm always trying to challenge myself to facilitate learning environments that produce diverse work from diverse learners.

# Collaboration with Learners

Why make curriculum for students when you can make curriculum with students? It's much more fun, and it removes a lot of the baggage of schooling from the equation. This doesn't mean that I abdicate my responsibility as a content-area expert--the opposite is true. I find that when I position myself as a resource and fellow explorer of students' goals, interests, desires, and learning needs, students make use of my skills in a way that's surprising, challenging, and (most importantly to me) different every year.

# Generative Creativity

This last one is the most important, and it's also one that often escapes our focus as teachers. When I say generative creativity, what I mean is that students make something new while they learn. It doesn't mean that they create "serious" art, and it doesn't mean that they create "innovative" things; it just means they create something that they hadn't created before, something expressive. I find that just saying "creativity" isn't specific enough--lots of things are creative, and this broad definition (a good definition! But a broad one) sometimes establishes a persmission structure for teachers to avoid facilitating learning experiences that focus on creation, on building an artifact that expresses students' learning. Why ask students to know something when they can create something (and come to know it that way) instead?